With the 2012 Summer Olympics in London on everyone’s minds this July, we’re continuing our series on the importance of hydration.

In Part 1 of 2 of this series on hydration, we noted via infotainment some considerations as to when it might be most appropriate to use just cool (not cold) water to rehydrate and when something more might be needed.

(Symbol of the five Olympic Rings which is in the Public Domain in the United States shown for identification purposes only courtesy of Wikipedia Commons).

We’ll get into a bit more of the subject of hydration in this infotainment blog post, including how to possibly estimate fluid losses during exercise; and potential hydration issues to be aware of before, during, and after sports or artistic performance activities.

Sweating is a process to enable the human body to cool down (via evaporation) during exercise. Sweating is much more effective for cooling purposes with lower humidity levels than with higher humidity levels.

Drinking adequate water-based fluids to replace sweat losses aids in cooling any body down, while dehydration actually inhibits the body’s ability to cool itself during and after exercise. Water is often enough for many “casual” athletes who engage in moderate intensity workouts lasting up to an hour in length.

Keeping track of approximate sweat & urine losses by appropriately weighing any athlete prior to and after exercise can be very helpful to make sure any athletes take action to stay hydrated. It is important to verify scale accuracy for each weighing using this approach to provide meaningful data to then prudently act upon.

Typically it is considered prudent to drink 16-24 oz of water-based fluid for every pound lost through sweating.

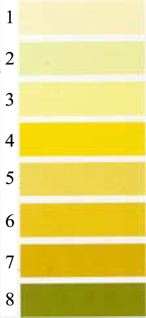

Checking one’s urine color has been suggested as another way to help gauge one’s hydration level since the mid-1990’s.

There is a Urine Color Chart (aka “Pee” chart) published by L. Armstrong, PhD, which is classically used as a reference visual for comparison purposes when evaluating urine color in a specimen cup. Armstrong, L.E. (2000) Performing in Extreme Environments, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL. It is being shown here only for identification purposes.

The difficulty with the practical use of the Urine Color Chart according to University of Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine professionals in a 2012 published article “Mythbusting Sports and Exercise Products” doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4848 is that it is considered potentially relevant only for a first morning urination at the start of a new day after a full night of rest and it involves a typical “clean catch” procedure mid-way through that first urination.

According to Armstrong, the urine color to aim for (which is associated with better hydration) is between 1-3. Most athletes should have caught signs of dehydration well before going to bed the night before, so the usefulness of the chart is a bit limited.

Lower, darker volumes of urine (colors 4 and higher) usually mean one might benefit from additional gradual hydration, (assuming one didn’t take any multivitamin products or certain medications prior to that urination being checked since some of those can “color” the urine).

A similar concept chart is available from the U.S. Army Public Health Command Heat: Are You Hydrated? Take the Urine Color Test (Poster).

Note: Since this post was first written, an infographic (13-HHB-1407-The-Color-of-Pee-Infographic_FNL-finalnm.jpg) from the Cleveland Clinic Urinary & Kidney Team back on 10/31/13 has become available titled “The Color of Pee” (or what the color of your urine says about you) accessible through a search via their clevelandclinic.org/HealthHub. The infographic source is identified as “Urine — Abnormal Color,” MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia, National Institutes of Health.

Advisement from the Cleveland Clinic towards the top of the infographic notes that “Urine may have a variety of colors. It usually ranges from a deep amber or honey color to a light straw color, with many golden variations in between. The color of urine can tell you a lot about your body. Here’s a chart of urine colors and what they indicate:”

We mentioned potential signs of dehydration in the Part 1 of 2 blog post on this subject. Aim to properly rehydrate by drinking typically 4-6 oz of water-based fluid every 15 minutes until the goal intake is reached. If your urine volume and/or frequency is lower and seems more concentrated, that usually indicates inadequate hydration so time to up the fluid intake appropriately.

(Water bottle image courtesy of crisderaud at rgbstock.com)

As we mentioned in Part 1 of 2 of this blog series, use cool (not cold) water to rehydrate if exercising for less than ~1 hour at moderate intensity.

If exercising for more than an hour or if any athlete sweats profusely or has a saltier sweat, then that athlete might need more than just water. The athlete might need a formula with some added carbohydrates and minerals (sodium and potassium) that function as electrolytes to replace fluid losses and electrolytes lost in sweating. As is appropriate, seek out a true commercially available sports drink, or diluted fruit or vegetable juice, or possibly low-fat or fat free milk, or even a home prepared isotonic sports drink such as was mentioned in Part 1 of 2 of this blog series.

There are even individuals who do well repleting carbohydrate and some electrolyte levels after exercise by consuming a ripe banana. We’ll address food considerations in relation to fuel for sports in another blog series.

Most people who engage in moderate intensity activity for up to ~45-60 minutes at a time will do just fine with plain, cool water to meet their hydration needs.

Although the media bombards the public with ads of professional athletes consuming all sorts of sports drinks, the reality for the average person is that they are not going to be training or competing at that higher intensity level of performance and thus would not need to turn to sports drinks per se. Of course, if a junior or other athlete is training or competing at a higher intensity level of performance, then follow suggestions appropriate for that level of sports involvement.

Some key points to keep in mind in summary of this two part blog series:

- Be alert to the potential warning signs of dehydration and be proactive to stay adequately hydrated in not only warmer weather, but during active times the rest of the year as well.

- Before beginning any strenuous or endurance exercise, always make sure that any athlete is already well-hydrated. Especially hydrate within the hour of engaging in any planned strenuous exercise activities by possibly consuming 8-20 oz of a cool (NEVER cold) water-based fluid; one “gulp” of water-based fluid is about equal to an ounce of fluid, give or take.

- Don’t count on thirst to trigger drinking of adequate water-based fluids–make it a priority for any athlete to regularly drink smaller amounts (4-6 oz) of cool (not cold) water-based fluids throughout the day–PREVENTION of dehydration is key! Some sodium content in water-based beverages and easy to eat and digest food items will also stimulate a sense of thirst.

- During and after exercise replete sweat and urine losses as soon as feasible.

- During the day when not in the middle of an exercise period, don’t forget that any athlete should also consume some water-based fluids with meals to help stay hydrated and help prevent episodes of dehydration during other times of the day when engaging in exercise.

- Minimize fluid losses during exercise and avoid excessive dehydration (>2% loss of body weight). Dehydration negatively affects athletic performance as in for every 1% loss of body weight in fluid an athlete will slow about 2%; dehydration causes early exercise fatigue, involves electrolyte imbalance, and may alter cognitive function including attention/focus as well as impair judgement when it comes to decision-making.

- Water-based fluids consumed with carbohydrate containing gels or carbohydrate containing simple snacks that are lower in fiber and easier to digest can help to get fluids & fuel to the muscles faster during exercise, so can potentially be considered for certain exercise breaks during longer duration and/or higher intensity sports practices and events.

Although a balanced diet rich in fiber overall is advocated by RDs, & state certified & licensed nutritionists, during exercise periods, athletes don’t want to draw the blood supply to the GI tract to deal with more complex digestion issues, so keep things simpler during exercise periods. Nutrition recovery after exercise ends often can optimally begin with 15-60 minutes following exercise. An upcoming blog post will discuss more about that.

It’s smart to be prepared before, during, and after exercise to stay properly hydrated. We’ve shared some infotainment in Part 1 of 2 of this blog series noting materials available through the Sports, Cardiovascular and Wellness Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group of the US based Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (SCAN); Sports Dietitians Australia (SDA); and Sports Dietitians UK of the British Dietetic Association (SDUK).

If you desire to have one-on-one input from a qualified Sports Dietitian aka Sports Nutritionist, we urge you to seek out same through an organization in the country where you are located using the channels we have suggested or similar ones available to you in your own country of residence.

During the Olympics, adequate hydration along with other factors of optimal nutrition for sports performance really can mean the difference between standing on the medal stand or just watching the ceremonies from the sidelines.

For the rest of us who may be “weekend warriors” or supportive parents or family members of children learning life lessons from sports involvement, it can mean that we do the best we can to support that athletic performance since there is truly nothing like experiencing a “personal best” in any sport or artistic performance category. Family experience in dance, ultra-running, and equestrian pursuits truly has taught us that.