In Part 1 of 2 in this blog post series, we addressed some infotainment after the release by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) in conjunction with the American Heart Association (AHA) of a scientific statement relative to nonnutritive sweeteners that the press considered newsworthy.

In Part 1 of 2 in this blog post series, we addressed some infotainment after the release by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) in conjunction with the American Heart Association (AHA) of a scientific statement relative to nonnutritive sweeteners that the press considered newsworthy.

(Sweetener image courtesy of wax114 at rgbstock.com)

On July 9, 2012, the ADA/AHA scientific statement provided a current use and health perspective on Acesulfame-K, Aspartame, Neotame, Saccharin, Stevia Glucosides, and Sucralose, which are 6 of the 7 nonnutritive sweeteners currently approved for use in the US by the FDA. The 7th nonnutritive sweetener also approved for use in the US by the FDA, luo han guo fruit extract, was not addressed in the scientific statement. At this time, certain other nonnutritive sweeteners such as Alitame, Cyclamates, Neohesperidine, and Thaumatin that are approved for use in the food supply in use in other parts of the world are NOT approved for use in the US as of the date of this blog post.

We noted in that Part 1 of 2 blog post that sweeteners fall into one of two major categories: Nutritive (which include sugar alcohols and various carbohydrates), or Nonnutritive.

Nutritive sweeteners can occur naturally in food items or can be added during food preparation or processing. They include carbohydrate as well as sugar alcohol forms.

Unlike nonnutritive sweeteners, nutritive sweeteners refer to sweetening products that contribute calories to the diet.

Some of these nutritive sweeteners are obviously alternatives to the most common table sugar (i.e. sucrose). These carbohydrate based nutritive sweeteners (NOT sugar alcohols) typically provide close to 4 calories per gram of product consumed. The sugar alcohol based nutritive sweeteners, on the other hand, are types of polyols formed from the partial breakdown and hydrogenation of edible starches. Sugar alcohols are sweet, but contribute ~ 0.2-2.6 calories per gram of product consumed.

In this Part 2 of 2 in this blog series, let’s review through infotainment some of what has been written about various nutritive sweeteners focusing on evidence-based facts and dispelling some fictional myths.

Of the carbohydrate based nutritive sweeteners, most people are familiar with the simplest of sugars that are either monosaccharides (single sugars such as fructose) or disaccharides (double sugars such as sucrose which is made up of fructose + glucose). There are also carbohydrate-based hydrogenated starch hydrolysates (HSH) which contribute ~ 3 calories/gram of product consumed.

For examples of nutritive sweetener terms that you might find on ingredient labels anywhere, including in summer Farmers Markets and regular retail stores please see our 17JULY2012 blog post on More Flavorful Nutritive Sweetener Options.

Many of these nutritive carbohydrate based sweeteners are actually composite sweeteners, for example, molasses is actually composed of about 53% sucrose, 23% fructose, and 21% glucose.

High fructose corn syrup (aka HFCS) has grown in both popularity and expanded use in the manufacturing sector. HFCS42 is the most common form of HFCS used in industry (made up of approximately 42% fructose and 58% glucose). Two other forms of HFCS used in industry include HFCS55 (meaning it is composed of 55%fructose and 45% glucose), and to a lesser extent HFCS90 (made up of approximately 90% fructose and 10% glucose).

HFCS42 is perceived by our tongues to be about 110% of the sweetness of table sugar aka sucrose; HFCS55 is perceived by our tongues to be about 125% of the sweetness of table sugar; and HFCS90 is perceived by our tongues to be about 160% of the sweetness of table sugar. Because manufacturers can use LESS total HFCS in making a liquid product in particular than they would of sucrose (table sugar) derived from cane or beets, yet our tongues perceive it as being just as sweet despite having less of HFCS used, it saves the manufacturer money to use HFCS.

Manufacturers have flocked to HFCS42 for use in liquid and solid food product production because of its lower cost compared to that of sucrose, because it is readily available, because it is perceived as being sweeter and thus less of it has to be used in say soft drinks, and because it retains moisture better in a number of baked goods products. It doesn’t caramelize as readily as sucrose, which could either be a manufacturing advantage or disadvantage–depending upon the desired application.

Some consumers are embracing newer alternative nutritive sweeteners showing up, especially in the health food marketplaces, such as coconut palm sugar (aka coconut sugar, palm sugar, or coconut sugar among other names). Coconut palm sugar is made from the sap of cut flower buds of the coconut palm. Thus if a tree is used for that purpose, there will be no coconuts coming later that season from that tree. It has been reported that the Philippine Coconut Authority in the Philippines is recommending growers to plant coconut trees especially for coconut sugar production, particularly the “dwarf” breeds that are shorter and can grow faster (an average of 5 instead of 10 years to reach maturity).

There are no Federal Guidelines that apply to sugar consumption and thus no Daily Value Percentage level (%DV) to be found on Nutrition Facts food labeling on the back of the package as a result.

The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans only allude to the idea that your health could benefit if you choose healthy foods that contain natural sugars most often and limit your consumption of foods high in added sugar content.

Each tsp. of sugar contains approximately 4.2 grams of carbohydrate and provides approximately 16 calories since fully digestible, non-fibrous carbohydrates provide approximately 4 calories/gram.

The AHA has published guidelines for a recommended daily intake of added sugar by adults. For most American women, it is recommended that no more than 100 calories (~6 teaspoons or ~25g) a day come from added sugar. For men, the recommendation is 150 calories (~9.5 teaspoons or ~38g) a day come from added sugar.

Contrast the AHA recommendations to what the government is reporting. Based on 2009 figures for per capita total consumption of caloric sweeteners by Americans, annual total intake was pegged at 130.7 lbs (including from sources such as refined cane & beet sugars along with corn sweeteners such as HFCS). Since there are 4.2 grams of sugar per tsp., that works out to be well over 38 teaspoons of sugar a day from all sources that the “average American” is consuming! This is significantly higher than what was noted in the 2004 Nutrition and Health Examination Survey (NHANES) report which listed only 22 tsp sugar/day.

Soda and sugary beverages are said to be the main sources of added sugar in the American diet, followed by sugars and candy. Other added sugars are found in cakes, cookies, and pies; fruit drink beverages (that are NOT mainly fruit juice, but rather contain a small percentage such as ~ 10% of actual fruit juice); ice cream and other dairy products that are more dessert-like including sweetened yogurt; and sugar sweetened grains (most often sweetened cereals, commercial waffles and toaster pastries, etc.). Sugars are also present (to an extent “hidden” one might say) in breads and other food items where consumers are less likely to suspect finding them. There is a whole category of “other” which is a source of added sugars in the American diet that include pasta sauces and more.

The high figures for total caloric sweetener consumption by Americans has caused various health agencies and organizations to look for ways in which Americans can reduce their total sugar consumption, especially through making more desirable choices concerning added sweeteners.

Reducing one’s consumption of added sugars from beverages is an easy place to start.

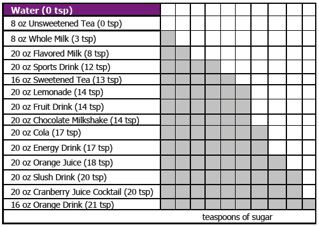

A graphic on pg 22 of Re-Think Your Drink (Be Sugar Savvy) pdf courtesy of Champions for Change compiled by them from data collected from the Calgary Health Region, BANPAC and USDA shows an example of just how many added tsp. of sugar many people are consuming as a result of the beverage choices they make each and every day.

The graphic also notes the issues with “portion distortion” whereby caloric content beverage consumption is by larger and larger cans, bottles, and super-sized beverage cups. (Mayor Bloomberg in NYC has supported the idea of a limit on the sizes of cups or containers of sugary beverage containers sold at food service establishments aka FSEs)

Some consumers will not accept the use of solely nonnutritive sweeteners in their soft drinks, etc., thus the trend right now is to “blend” nonnutritive sweeteners with nutritive sweeteners (primarily sugars) in the latest line of beverage products being released by industry to you as a potential consumer of them.

The other major category of nutritive sweeteners is compromised of sugar alcohols. Some of the sugar alcohol based nutritive sweeteners you may have heard of include, but are not limited to, erythritol, isomalt, lactitol, maltitol, mannitol, polyglycitol, sorbitol, and xylitol.

Scientists frequently refer to sugar alcohols as polyols. In nature, they are naturally found in berries, applies, plums and some other food sources. In the food industry, they are manufactured from carbohydrates from the partial breakdown and hydrogenation of edible starches.

You can find a Sugar Alcohols Fact Sheet at the Food Insight website. Please be aware that xylitol is NOT safe for pets, particularly canines (dogs) so do NOT allow access to any food item containing xylitol, especially when it comes to much smaller size dogs where dose size can be very critical.

An example of a retail xylitol product is Ideal® No Calorie Sweetener. It is a blend of xylitol, dextrose, maltodextrin, and a small amount of sucralose designed to measure cup-for-cup in terms of contributing to volume and texture to replace table sugar (sucrose) in recipes providing 53 grams of carbohydrates equal to 202 calories.

Polyols can be partially, but not completely digested by the body, thus on average, they provide half the calories of various sugars and longer chain digestible carbohydrates. That means they contribute only about 2 calories per gram of product consumed as previously noted. If ingested in large quantities, some polyols, such as sorbitol, may produce gas and create discomfort in the GI tract and may even lead to diarrhea episodes in some individuals, based on dose consumption. Thus you may find that food items which contain a significant quantity of certain polyols/serving on their package label may also contain a statement noting “Excessive consumption may have a laxative effect.”

Note that these products might also be found in cough and cold syrups and other liquid medications such as antacids.

Sugar alcohols are used as sweetening substitutes for “sugars” in “sugar-free” products such as candies, cookies, chewing gums and other reduced-calorie food items.

They also provide desired bulk to some food items. They do not have the cavity-promoting features of sugars. Sugar alcohols also result in a lower rise in blood glucose and insulin levels when compared with sugars and other nutritive carbohydrates. Sugar alcohols are also used in food products as alternatives to sugars precisely because they contribute minimal calories and minimally affect blood glucose levels.

The FDA is charged in the US with the responsibility to determine the safety of substances that are added to our food supply. Although not everyone will agree with the findings of any expert panel that reviews the literature and other reported data on safety parameters, in the end, the FDA decides if a substance should be considered Generally Recognized as Safe or receive what is called a GRAS classification status.

Science professionals also know that researchers who belong to the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) often do their own review of the literature. Elsewhere, the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JEFCA) {Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the World Health Organization (WHO)} also reviews nonnutritive substances data when determining what is acceptable at a particular level of intake when it comes to human safety of use.

Terms you will see associated with nonnutritive sweeteners include Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) and Estimated Daily Intake (EDI) for use of the sweeteners in food and beverage items. The ADI represents the amount of an ingestible food ingredient that can in theory be safely consumed on a daily basis over an entire lifetime–hopefully without incurring any health risk. Studies thus far have lead the FDA to believe that the EDI use of low-calorie sweeteners does not approach the ADI threshold level of intake in terms of safety.

There is an older pdf overview of “Low-Calorie Sweeteners and Health” published by the International Food Information Council Foundation (IFICF) that you can check out to learn more about how the FDA determines ADI and EDI–see the section on “Anatomy of a Sweetener Approval” per se. That pdf looks at Acesulfame-K, Aspartame, Neotame, Saccharin, and Sucralose. Stevia glucosides aka steviol glycosides aka steviosides and Rebaudiosides were not FDA GRAS approved at the time the IFICF publication had previously gone to press.

The ADA/AHA scientific statement mentions ADIs for each of the nonnutritive sweeteners and we’ll summarize that info in a handout we’ve put together for you.

In the end, the choice is always yours as a consumer to decide what you will or will not buy and serve to yourself, your family and your friends. Stay informed and make your choices accordingly.

There are times when less might just be a better choice, especially when it comes to added sweeteners of any type.

If you are interested in some specifics about each of the nonnutritive sweeteners, you are welcome to go to our Facebook page where you will find a free gift download available for our fans.